Dog Park Danger: How To Spot Predatory Drift Before It’s Too Late

The dog park. For many of us, it’s a slice of heaven for our four-legged friends—a place of joyous romps, floppy-eared greetings, and endless tennis balls. We love watching our dogs run free, socialize, and just be dogs. But within this happy chaos lies a potential danger that many well-meaning owners don’t know about: predatory drift.

It’s a scary-sounding term, but understanding it isn’t about fear-mongering. It’s about empowerment. Predatory drift is not a sign of a ‘bad dog’ or aggression; it’s a primal instinct, hardwired into their DNA, that can surface unexpectedly. It’s that chilling moment when a playful chase suddenly shifts, and one dog begins to view the other not as a playmate, but as prey. Knowing how to spot the subtle signs before that switch flips is one of the most important skills a dog owner can have. Let’s dive in and learn how to keep the dog park fun and, most importantly, safe for everyone.

Unpacking the Instinct: What Exactly is Predatory Drift?

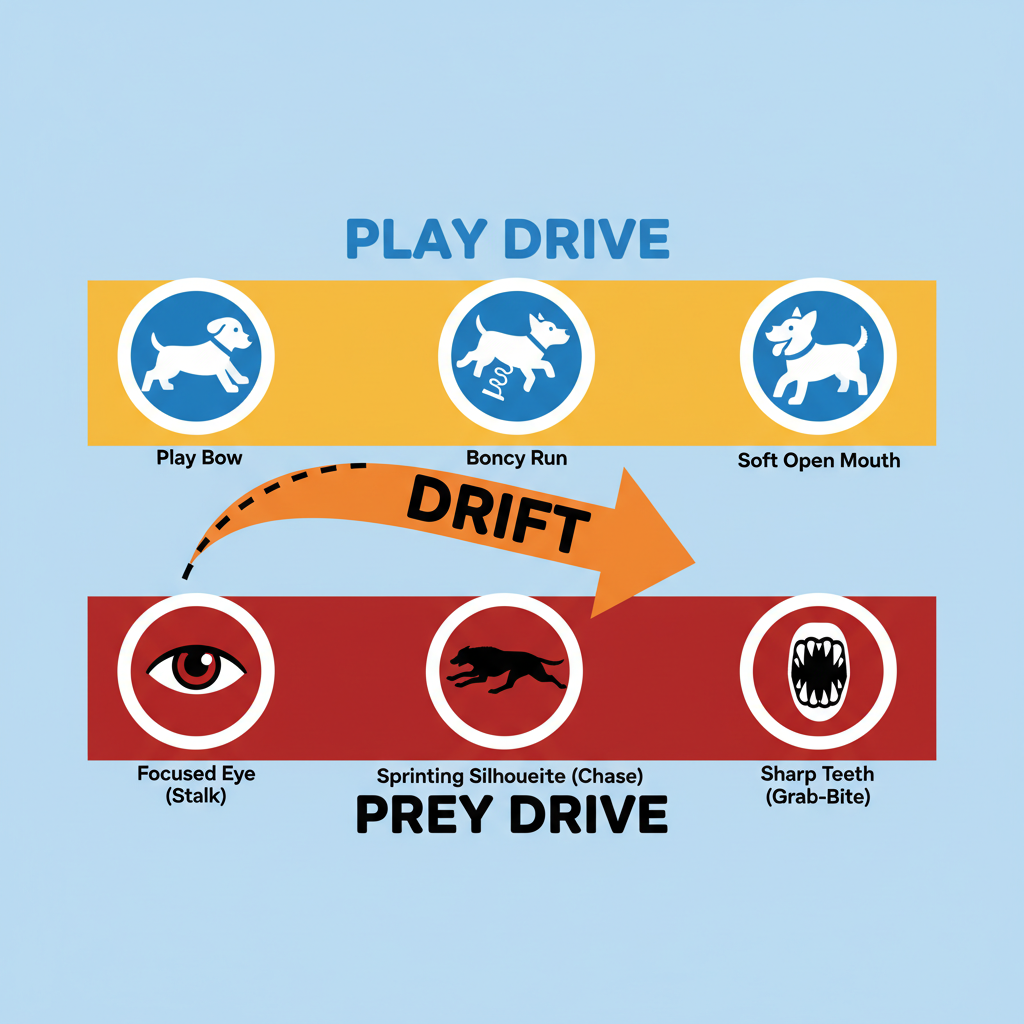

So, what is this phenomenon we call predatory drift? At its core, it’s when a dog’s ‘play drive’ gets hijacked by its ‘prey drive’. All dogs, from the tiniest Chihuahua to the grandest Great Dane, are descendants of predators. That instinct to hunt is still there, usually buried under layers of domestication and training. The predatory sequence is a specific, ingrained pattern: search, stalk, chase, grab-bite, kill-bite.

During normal play, dogs might mimic these behaviors. They ‘stalk’ each other from behind a bush, engage in a wild game of chase, and mouth each other gently. It’s all in good fun, with lots of breaks, play bows, and role-swapping. Predatory drift happens when that mimicry stops, and the real instinct takes over. The ‘game’ becomes a one-sided, silent, and intensely focused pursuit. The dog is no longer playing; it’s hunting.

This shift can be lightning-fast and is often triggered by specific stimuli—like a smaller dog running away at high speed, or the high-pitched yelp of a dog that gets accidentally tumbled. This trigger can flip a switch in the brain, causing the dog to ‘drift’ from play into a predatory mindset.

It’s crucial to understand this isn’t the same as dog-on-dog aggression, which is often rooted in fear, resource guarding, or reactivity. Predatory drift is quieter, more focused, and often lacks the warning signals of aggression like growling or snarling. That’s what makes it so dangerous—it can look like play until the very last second.

The Warning Whispers: Early Signs of Predatory Drift

A dog on the verge of drifting will give off signals, but they’re often subtle and easily missed in the chaos of a dog park. Learning to read this silent language is your first line of defense. Keep your eyes peeled for these telltale signs, especially from a single dog directed consistently at another:

- The Stare and Freeze: The dog’s play suddenly stops. It freezes, often lowering its head and body, and locks its eyes onto another dog with a hard, unwavering stare. Its body will be stiff and rigid, vibrating with intensity. This is not a playful pause; it’s a target lock.

- Silent Stalking: Instead of a bouncy, inefficient play-chase, the dog’s movements become fluid, quiet, and deliberate. It might use a low-to-the-ground, cat-like stalk to approach its target. The happy, panting mouth closes, and the face becomes tense.

- Lack of Play Signals: All the normal signs of fun disappear. There are no more play bows, no goofy expressions, and no reciprocal play. The dog is ignoring all signals from the other dog, especially appeasement signals like tail tucking or rolling over.

- Targeting Specific Dogs: The dog isn’t just playing with anyone; it’s fixated on one specific dog. This target is almost always smaller, faster, or acting more ‘prey-like’ (e.g., running frantically, yelping).

- The Chase Changes: A play-chase is often loopy and inefficient. A predatory chase is a straight, silent, and incredibly fast line aimed at cutting off and running down the target. The goal has shifted from ‘chase for fun’ to ‘chase to catch’.

Red Flags at the Park: Identifying High-Risk Situations

While any dog can exhibit predatory drift, certain situations dramatically increase the risk. Being aware of these environmental triggers can help you decide if today is a good day for the park, or if it’s time to leave.

Common Triggers Include:

- Significant Size Discrepancy: This is the biggest red flag. When very large dogs are in a high-energy play session with very small dogs, the risk skyrockets. The size, speed, and movements of a small dog can easily trigger a large dog’s prey drive. Many parks have separate small dog areas for this very reason—use them!

- The Pack Mentality: Predatory drift is more likely when multiple dogs start to chase a single dog. The group excitement can quickly escalate, and dogs can feed off each other’s arousal, leading to a dangerous ‘pack chase’.

- High-Pitched Noises: A sudden yelp or squeal from a dog, whether from fear or from being accidentally stepped on, can be a powerful trigger. It sounds like injured prey, and it can cause that predatory switch to flip in an instant.

- Over-Arousal and Crowds: A chaotic, overcrowded park where dogs are amped up and running wild is a breeding ground for problems. When a dog’s arousal level (excitement) is already at a 10, it doesn’t take much to push it over the edge into a reactive or predatory state.

Intervention Protocol: How to Safely De-escalate

You see the signs. A dog is locked on, the chase has turned serious. What do you do? Acting quickly and correctly can prevent a tragedy. Panicking will only add to the chaos.

- Make a Loud, Startling Noise: Don’t scream. Use a sharp, loud sound to break the dog’s concentration. A loud, firm ‘HEY!’ or a sharp double-clap can sometimes be enough to interrupt the sequence. Some owners carry a whistle or a small air horn for this purpose. The goal is to startle, not scare.

- Body Block (If Safe): Move calmly and confidently to place your body between the pursuing dog and its target. Do NOT grab the dog’s collar, as this can lead to a redirected bite. Simply becoming a physical barrier can break the line of sight and interrupt the chase.

- Recall and Leash Up: Use your strongest recall command. As soon as you have your dog’s attention, call them back and immediately leash them. If your dog is the one pursuing, this is your responsibility. If your dog is the target, get them leashed and move them to a safe, neutral area away from the action.

- Leave the Park: This is non-negotiable. Once a dog has crossed that threshold, its adrenaline is high and it’s not safe to let it return to play. The best and safest course of action is to calmly leash your dog and leave the park for the day. It allows your dog to decompress and prevents a second, more serious incident.

My Dog Did This… Is He a ‘Bad Dog’?

If you’ve witnessed your own sweet, loving dog exhibit signs of predatory drift, it can be a deeply upsetting and confusing experience. You might be feeling embarrassed, scared, or even angry. The most important thing to remember is this: your dog is not a ‘bad dog’.

Predatory drift is not a reflection of a dog’s character or the love it has for its family. It’s a hardwired, instinctual behavior that has been selectively bred into many breeds for centuries—think of terriers bred to hunt vermin or hounds bred to chase game. It doesn’t mean your dog is aggressive or that it will bite people. It simply means that your dog has a strong prey drive that can be dangerously triggered in specific, high-arousal environments like a dog park.

Accepting this is not an excuse, but an explanation. It’s the first step toward responsible management. It means acknowledging that the chaotic, unpredictable environment of a dog park is not a suitable or safe place for your dog to be. And that’s okay.

Instead of feeling guilt, reframe it as an opportunity to understand your dog on a deeper level. Now you know their triggers, and you can provide them with safer, more structured forms of exercise and socialization that set them up for success.

Conclusion

The dog park can be a wonderful resource, but it comes with inherent risks. Predatory drift is one of the most serious, yet least understood, of those risks. By learning to recognize the subtle shift from play to prey, identifying high-risk scenarios, and knowing how to intervene, you’re not just protecting a potential victim—you’re also protecting your own dog from a tragic mistake driven by pure instinct.

Remember, being a responsible dog owner isn’t about hoping for the best; it’s about preparing for the worst. Your dog relies on you to be their advocate and keep them safe. Sometimes, that means making the tough call to say, ‘The dog park isn’t for us.’ And in its place, you can explore wonderful alternatives like structured playdates with known dog friends, scent work classes, or long, peaceful decompression walks on a long line. Your bond with your dog will be all the stronger for it.